Historical works continue to inspire modern artists and nourish faith

Written by Josh Tiessen

This past year I enrolled in a master of art history program at the University of Toronto. As a fine artist, I thought it made sense to study the famous artists, styles, and movements of the past, including those outside my cultural background, like Chinese painting and Arabic architecture.

It’s striking that to understand the narratives, symbols, and motifs employed by artists of the past, we need to know the Bible. Without reading the Parable of the Prodigal Son, how could you fully appreciate Rembrandt’s rendition of a loving father embracing his wayward son? Without reading Jesus’ birth narratives in Matthew and Luke, what would one make of all the paintings featuring a mother and child with halos?

Conversely, studying art history can also grow our faith and sanctify our imagination. Art is a prism that has the potential to teach us something about God.

In my own paintings, I have been experimenting with shaped wood panels for the past ten years, breaking away from the traditional rectangular format. I have painted on circles, triangles, pointed arches, and whimsical contours. My painting Auguries of Innocence II is shaped like a Celtic cross. It features an endangered Madagascan Moon Moth, showing how Christ suffers with all of creation, longing for its redemption from habitat destruction.

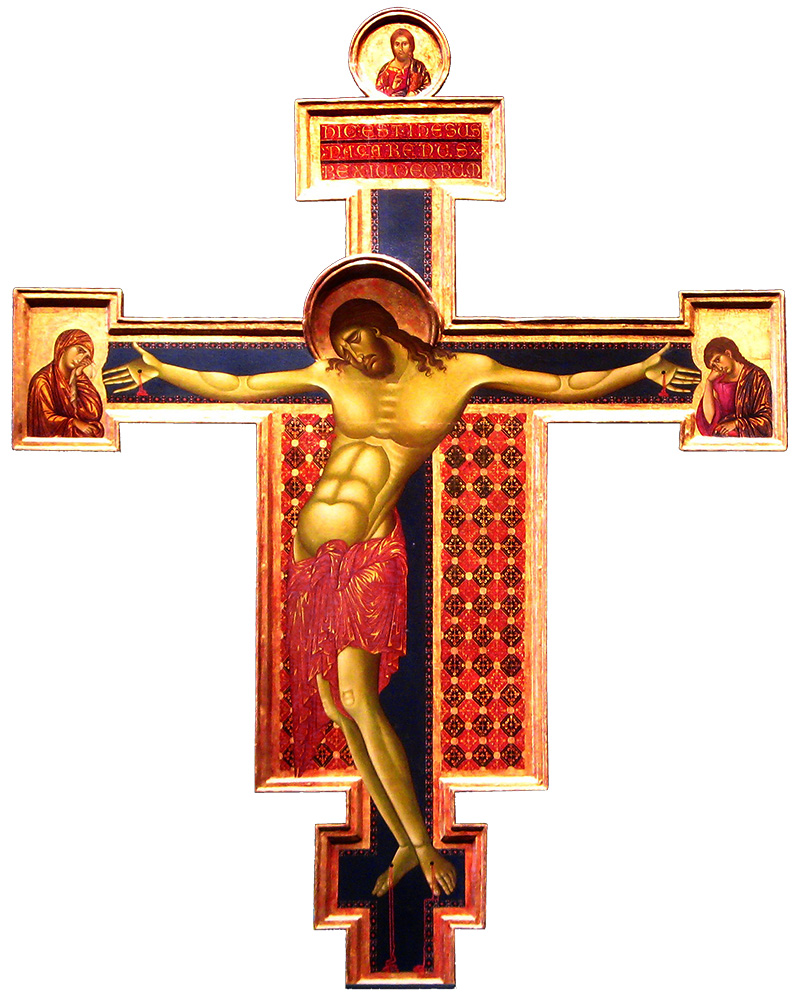

My interest in non-rectangular formats draws upon Medieval and Renaissance iconography, and I have enjoyed learning about its theological significance. For instance, one of the earliest shaped panel paintings in the Medieval Age was the crucifix, painted by Italian artists like Cimabue and Giotto.

They share common motifs such as a circular “roundel” on top, which usually features a portrait of God the Father blessing His son, and a sign just below, inscribed: “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.” On either side of the cross appear rectangular panels, with the Virgin Mary on the left and John the Evangelist on the right.

One of the earliest examples is the Franciscan crucifix called the Christus triumphans or Triumphant Cross in which Christ is pictured upright and victorious, overcoming death. There is also the Christus patiens or Sorrowful Christ in which Jesus’ body is bent and his head droops with eyes closed.

According to Richard Viladesau in The Beauty of the Cross, these differences reflect a theological shift, as originally there was a greater emphasis on the triumph of Christ over death through his resurrection. Beginning in the 12th and 13th centuries, more attention was paid to Christ’s suffering on the cross as a sacrificial payment for sin to accomplish salvation.

Today, in many contemporary Protestant churches we usually have a cross without Christ’s body, to represent that he rose from the grave and has ascended on high. While we may be uncomfortable seeing Jesus’ bloodied corpse, perhaps sometimes we need a visual reminder of Christ’s sacrifice, as he continues to bear our sufferings today.

During the Renaissance, shaped art took the form of the altarpiece, a multi-panel painting that hung above the altar at the front of the church. For example, the famous Insenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald featured painted winged doors that remained closed except for holy days. I have used this sacred framework in my paintings Rise Up and Agnus Dei, which similarly have functional doors.

Another common altarpiece is the pointed gothic arch which, like gothic cathedrals, symbolizes lifting our souls upward. I used this shape in my Creation Cathedralas a way to show the sacramental capacity of the redwood forest.

The Madonna and Child are often featured in Renaissance altarpieces, particularly those shaped as a lunette, a rectangular form with a domed top. Mary is also depicted in the circular “tondo” form. According to one theory, both of these shapes symbolize Mary’s innocence, wisdom, and perfection, since the circle is a shape that represents wholeness.

While Protestants see Mary as a humble servant of the Lord and in need of salvation like any one of us, there’s nothing wrong with honouring her faithfulness in bearing the Son of God. She remained with Jesus at the foot of the cross while almost all of his disciples deserted him, and was a leading voice among the early Apostles.

In my work Sophia, I depicted Lady Wisdom from Proverbs. I chose the circular tondo for a similar effect to the Madonna paintings.

Shaped art went out of fashion after the Renaissance. It wasn’t until the early 20th century when Russian Suprematist artists and New York abstract artists began experimenting with shaped canvas yet again. Many credit medieval icons and altarpieces as being their inspiration. The Cross continues to be a popular (and sometimes blasphemed) motif among contemporary artists, including those without religious affiliation.

Art history might be one of the few domains within our largely secular culture where people are still engaging with the Christian faith. Perhaps we Christians should pay a little more attention to it ourselves.

Josh Tiessen is a fine artist, speaker, and writer based in Stoney Creek, Ont. Read more of his columns.